The Assembly of the Dead

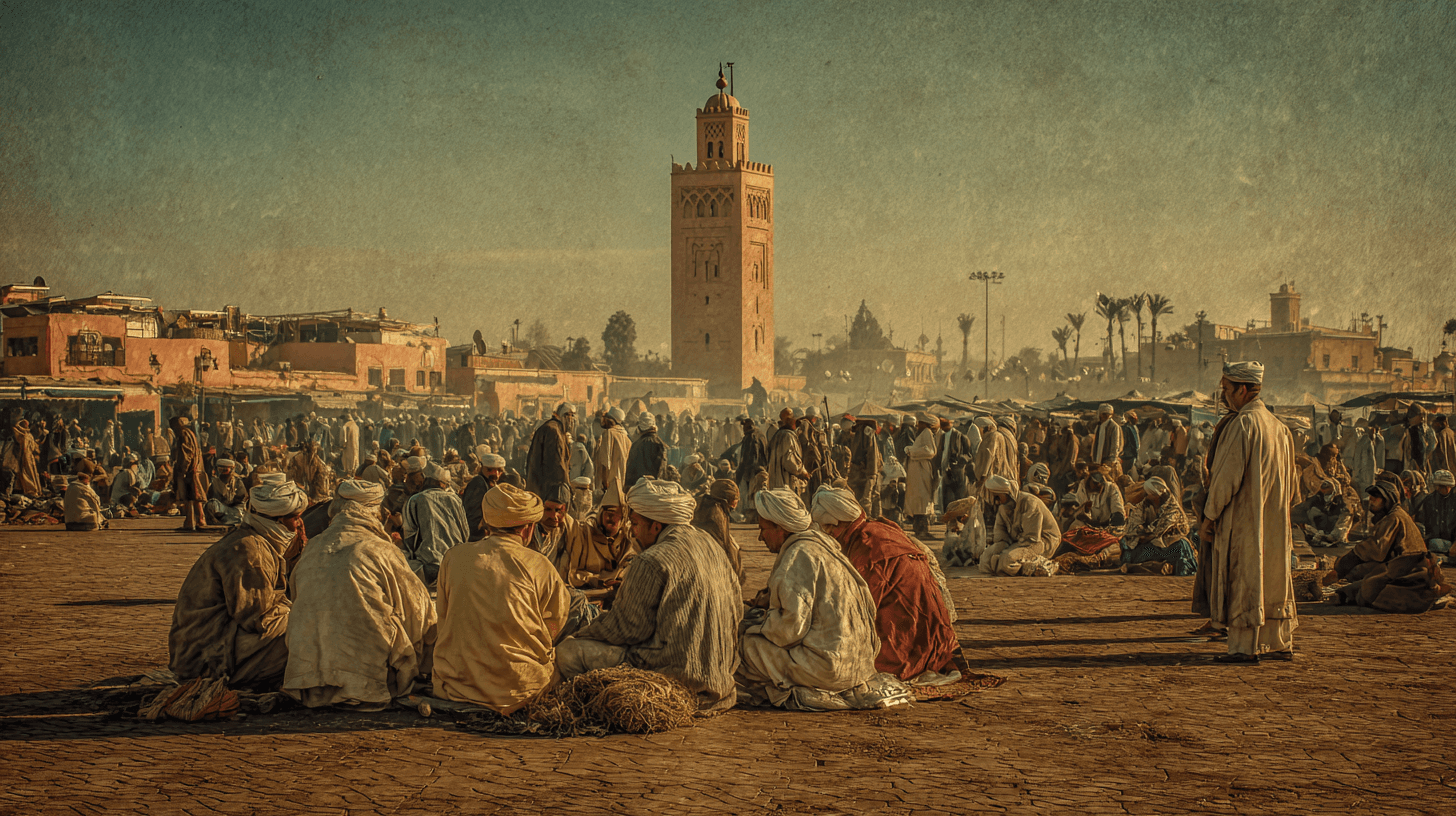

A thousand years of spectacle on one square

The name means what it says.

Jemaa el-Fna. The Assembly of the Dead. For centuries, this is where Marrakech displayed the heads of executed criminals and defeated enemies on poles — a warning to anyone entering the city through its main gate. The severed heads faced outward, watching the caravans arrive from the Sahara.

The square was born with the city itself. When the Almoravids founded Marrakech in 1062, they needed a gathering place outside the palace walls — somewhere traders could unload their camels, somewhere the sultan's justice could be witnessed by all. The space that would become Jemaa el-Fna served both purposes. Commerce by day. Executions when required.

By the twelfth century, the Almohads had built the Koutoubia Mosque at the square's edge — its minaret still the tallest structure in Marrakech, still the compass point that orients the entire medina. The old palace was torn down. The executions continued. But something else was happening too.

Storytellers had discovered that a crowd gathered for a beheading would stay for a tale.

The halqa — the human circle that forms around a performer — became the square's organizing principle. Not architecture. Not planning. Just people arranging themselves around whoever had something worth watching. Snake charmers. Acrobats. Herbalists selling cures for impotence and heartbreak. Tooth-pullers with pliers and a pile of extracted molars as proof of their skill.

The storytellers were the aristocrats of this economy. They performed in episodes, like serialized novels, stopping at the climax and passing the hat. If you wanted to know whether the hero escaped the djinn's palace, you came back tomorrow. Some tales ran for weeks. Audiences followed their favorite narrator the way we follow television series — except the story changed each night based on the crowd's reaction, the teller's mood, the news from the caravan routes.

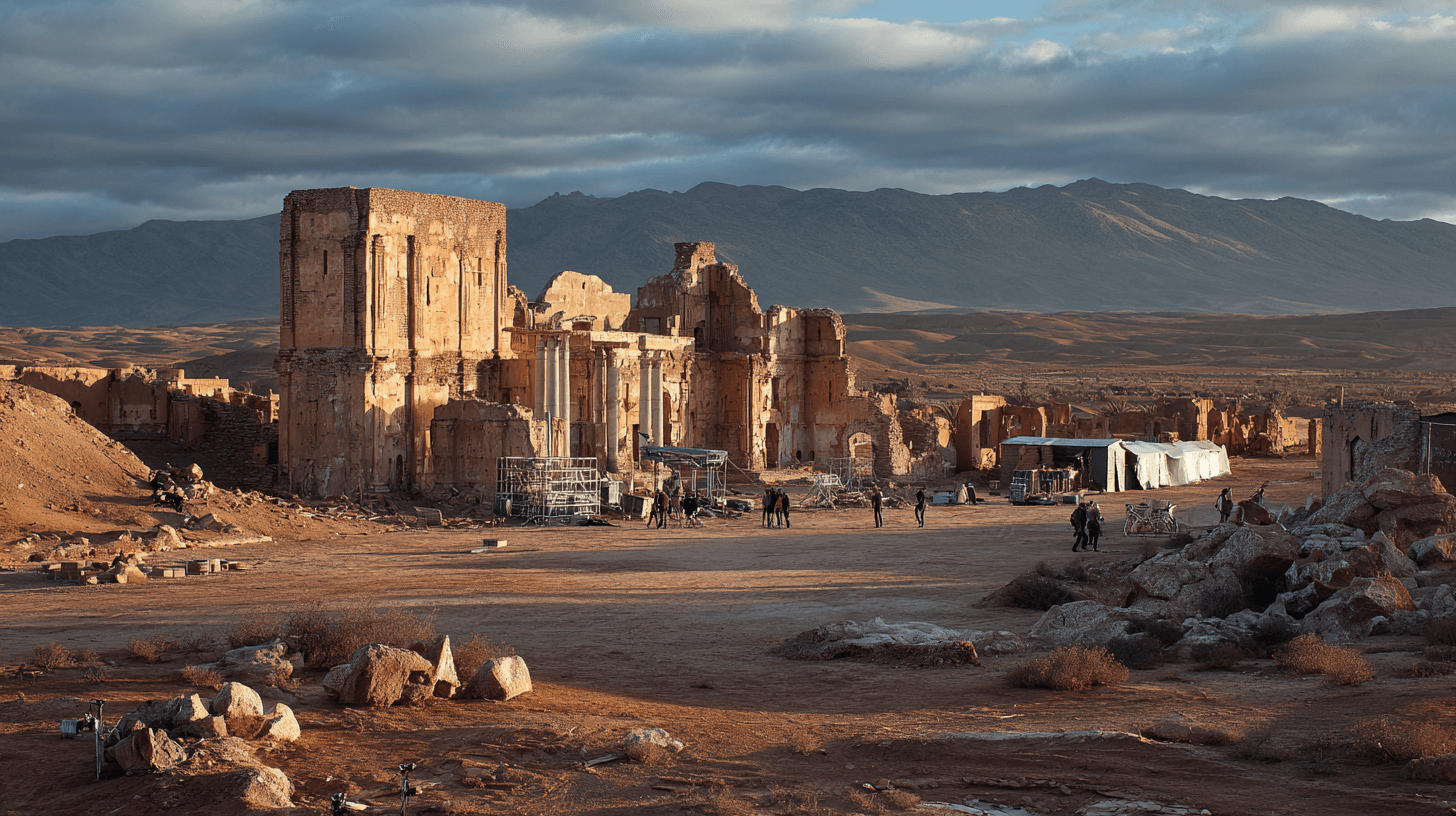

In 1956, Alfred Hitchcock arrived with James Stewart and Doris Day to film "The Man Who Knew Too Much." The director had already made one version of the story in 1934. For the remake, he wanted color, he wanted scope, and he wanted that square.

The murder scene happens in broad daylight, in the middle of the crowd. A French spy, stabbed, staggers through the snake charmers and collapses into Stewart's arms. With his dying breath, he whispers a secret about an assassination plot. The camera captures Jemaa el-Fna exactly as it was — the acrobats, the musicians, the mint tea sellers — and exactly as it had been for nine hundred years. Hitchcock understood: this was a place where anything could happen in plain sight, where a man could die and the show would continue.

Doris Day sang "Que Sera, Sera" in that film. It won the Oscar for Best Song.

Sixty-four years later, Charlize Theron walked through the same square for "The Old Guard." The Netflix film used Jemaa el-Fna as Morocco — and as Afghanistan, and as everywhere ancient that the immortal warriors had passed through across their centuries of existence. The square doubled for multiple countries because it looks like it has always existed, because it feels outside of time.

UNESCO named it a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2001 — the first cultural space in the world to receive that designation. The Spanish writer Juan Goytisolo had fought for the recognition after developers proposed building a parking garage underneath and a fifteen-story tower beside it. He argued that the square's value wasn't in its stones but in what happened on them.

The halqa still forms every evening. The storytellers are fewer now — five where there were once twenty, competing with television and phones for attention. But the snake charmers still play their pungi flutes. The henna artists still wait with their syringes of paste. The food stalls still fill the air with smoke from a hundred grills as the sun sets behind the Koutoubia.

The heads no longer watch from poles. The assembly has found other reasons to gather. But the name remains — a thousand-year-old reminder that this square has seen everything, survived everything, and will still be here when we are gone.

The Facts

- •Founded 1062 with Marrakech itself — among the oldest continuously used public squares in the world

- •Name means 'Assembly of the Dead' — site of public executions from 12th-14th centuries

- •Alfred Hitchcock filmed 'The Man Who Knew Too Much' (1956) here with James Stewart and Doris Day — 'Que Sera, Sera' won Best Original Song Oscar

- •Charlize Theron filmed 'The Old Guard' (2020) here — Netflix reported 78 million households watched in first month

- •UNESCO's first-ever 'Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity' (2001)

- •Spanish writer Juan Goytisolo saved the square from developers in 1996

- •Only 5 traditional storytellers remain where there were 20 in the 1970s

- •Koutoubia Mosque minaret (77 meters) has anchored the square since 1147

Sources

- UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, 'Cultural Space of Jemaa el-Fna Square' (2008)|Wikipedia, 'Jemaa el-Fnaa' — historical documentation of name origins and executions|Movie Locations, 'The Man Who Knew Too Much' (1956) filming locations|Netflix press release, 'The Old Guard' viewership statistics (October 2020)|Juan Goytisolo advocacy documentation, UNESCO 1997 consultation